Everyone knows that the two basic tools of the gardener from time immemorial are the watering can and the hoe. This year I am tossing away the watering can, at least at one of my gardening spots, and entering the strange world of water-free growing.

| I know you are thinking this when I say dryland farming. Read on. This is actually a hopeful, happy article, not some gut punch on climate change, though dry farming may actually be an adaptation to a less watered world. |

Actually I’m not the least bit anxious about the result, rather I’m psyched to be able to return to my favorite way of growing tomatoes – dryland. Dryland farming or dry farming is as it implies – using little or no supplemental water to grow a crop…supplemental being, in this case, anything that comes out of a hose. In western Oregon, we get plenty of rain from October to July, but nary a drop from mid-July to mid-October, so this waterless thing is no kid play. You will probably have figured that I cannot mean the rooftop garden. Up on the Noble Rot roof, if we don’t keep plenty of water on our shallow beds pretty much all summer long, we’ll have some sad-looking, heat-fried greens in a jiffy, and I’ll probably earn a nice pink slip to go with them (as in, “Get lost, farmer!”). But perhaps you haven’t heard that the Noble Rot has opened a new café, the Noble Oni, located at the Oregon College of Art and Craft. (Yes, I know…Noble Oni…No Baloney…har, har, har. Look, I only garden for these guys. I had no input on the name.) Well, anyway, down by the ceramics studio there is a fairly good piece of empty land, and my friend chef Leather Storrs and I immediately agreed that we must grow tomatoes.

That this site is fairly far away from my daily route and that we had some room to spare suggested the low-input, high-flavor option of drylanding. The basic premise is this: left to their own devices, many plants can forage widely and deeply for water, and if weed competition is kept to a minimum and the target plants are spaced properly so as not to compete with each other, they can pretty much take care of business on their own, without much pampering from the gardener. Plenty of water is stored in the soil, and eventually the dried-out upper layer of soil provides a kind of protective crust for what’s below…provided it’s not “mined” by some other plant’s taproot. As far as a succulent fruit like the tomato goes(Wha? Fruit? You thought tomatoes were a vegetable, right? They’re BOTH – botanically fruit, legally a veggie….look it up!), this kind of neglect, nay abuse, may actually prove stimulating. While yields may be lower than their watered brethren, the flavor is much more concentrated (makes sense, less water to dilute taste)…which is exactly the kind of thing to which a discerning palate, such as a chef’s, responds.

One warning: water helps calcium move through plant tissues, and when tomatoes don’t get enough calcium, either from an actual soil deficit or from a water deficit, which dissolves and moves the calcium, they can get a rather gross-looking condition called blossom end rot.

Usually blossom end rot is caused by vacillations in the watering regime, as in getting lots of water this week but drying out the following week. It can be especially bad in containers, which are susceptible (via the gardener, of course) to irregular watering. Some websites warn that drylanding tomatoes could result in blossom end rot, in which case you’d have superior-tasting, gross-looking tomatoes.

With past dryland experiments, which I conducted during my salad days at Zenger Farm, I did not have much blossom end rot trouble because the plants appeared to gain steady access to the very consistent water supply held in the subsoil. Again, this water supply remains consistent and steady only if there is no significant weed pressure to compete for that water, so keep that in mind. When I did this before, the tomato plants were the only green in a sea of brown soil…as in weed free. I plan to do the same kind of aggressive weeding this year.

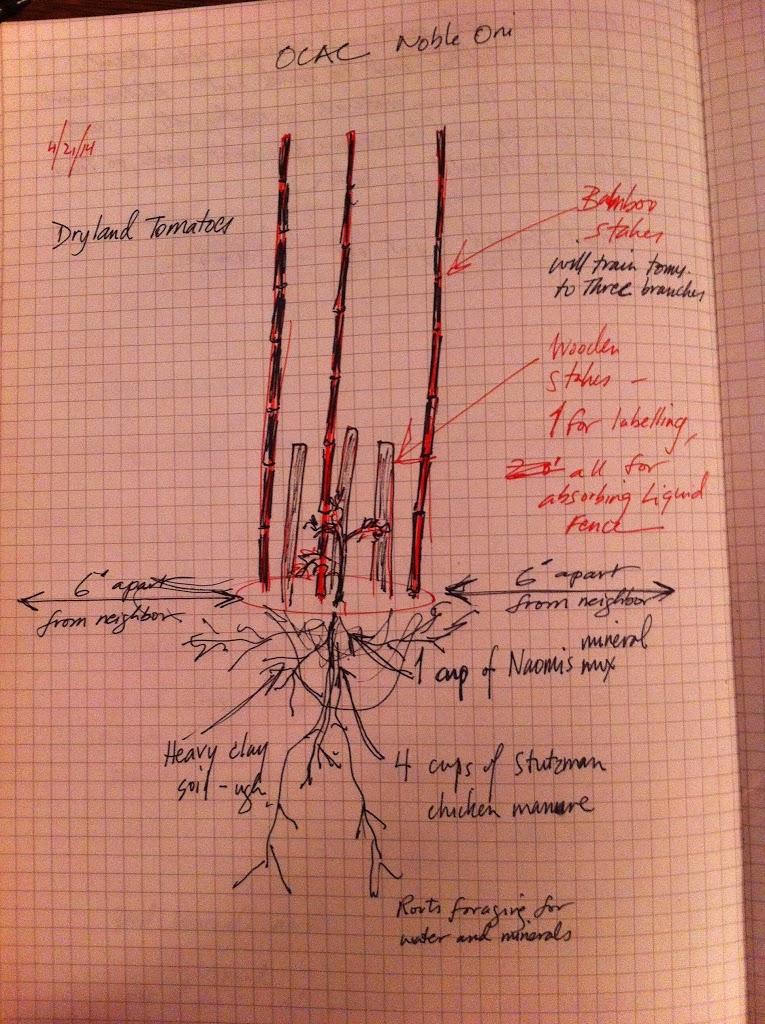

My little sketch below gives the scheme for each tomato, planted 6′ apart in a line from its neighbor. Into a large-ish hole in the rather gooey clay soil, I threw one cupful of a mineral mix and four cupsful of well-composted chicken manure, all of it stirred into the clay, if one can be said to stir anything well into clay soil. Into the prepped hole went a large tomato transplant, started indoors around mid-February. Immediately upon planting I sank three stout bamboo stakes around the plant, which will become the support for three vines I will allow to grow from the plant (more on pruning and training in a later post). I also put three short wooden stakes around the plant, one as a label for the variety (in Sharpie) and the other two as mere porous surfaces to catch and hold a product called Liquid Fence, which is a nicely-packaged yet vile-smelling blend of, basically, putrescent eggs, said to effectively repel deer and rabbits. I’m two weeks into a once-a-week-for-three-weeks-then-once-a-month nauseating spray routine, which I truly hope will keep off any marauding deer. I’ll also need to do some barbaric weed whacking in another week or so to really create a circle of death and destruction around each plant until summer really arrives and the surrounding grasses die off naturally. Then, truly competitor free, these toms can reach for their concentrated peak (pique?) of flavor.

|

| Ahh, garden plans always look so perfect on paper. Notice I didn’t draw in any deer. |

,

Anyway, it’s all a bit more humble than I make it sound – actually only 18 tomatoes, but the design is scalable depending on how much land you have, and in this scheme, one tomato plant goes a long way!

|

| Tomatoes as objets d’art at the Oregon College of Art and Craft in Portlandia. |

So watch with me and prepare to enter the Twilight Zone of farming, where water is withheld and flavor actually improves. And if you must know more, read this:

or Steve Solomon’s excellent short book on the subject, Gardening Without Irrigation